When Kelly Hail was diagnosed with breast cancer and forced to undergo a double mastectomy, her body changed beyond recognition. Here, she writes about how she came to accept her scars not as disfigurements, but as marks of her personal struggle.

My Journey Starts Here

When I was first diagnosed with breast cancer, in July 2018, scarring wasn’t at the forefront of my mind. Fear, and then survival, were my only thoughts. I had no choice but to navigate a life that required living. I chose to value the present, cherishing my two boys, my husband and dear friends, and embracing the simplest of pleasures that had previously been hidden in plain sight. With each personal setback and challenge I gained a thin layer of perspective, piling those layers one on top of the other until life began to come into focus.

My life since then has often felt fragmented. I have felt besieged and overwhelmed. Profound, life-threatening experiences have circled me, all while I tried to continue to lead an ordinary life. That turned out to be the critical step for me: recognising that it was no longer an ordinary life. The rules of life had changed, and I needed to accept that fact.

Putting on a Brave Face…

Over the last two years, I have been challenged too many times to count. In my fight against stage-two breast cancer I’ve always tried to put on a brave face despite a double mastectomy, prolonged chemotherapy, radiotherapy and lymphoedema. Complications with my treatment required additional operations, including a latissimus dorsi flap procedure. I won’t bore you with the medical details, but it involved a nine-hour operation, taking muscle and tissue grafts from my back to rebuild my left breast after my implant was compromised by an infection.

More recently, in April 2020, in the first week of national lockdown in the UK, a large tumour was discovered in my uterus. I subsequently underwent the first of my two operations during lockdown, and, after an agonising five days, I learnt that the tumour was benign. A few weeks later, I contracted cellulitis in my lymphoedema arm, which turned to septicaemia, requiring nine days in hospital and the replacement of my breast implant for a third time.

In total, I underwent four procedures in the space of three months, whilst Covid raged on around me. I will always need to wear a compression sleeve on my left arm to counteract the effects of lymphoedema, which causes swelling. My body has changed beyond recognition but I know I am one of the lucky ones. Counterintuitively, my imposed stillness in hospital led to action. My battle plan was cemented: to accept my situation, face my fears, rebuild and carry on.

After lockdown I escaped to the mountains, to Chamonix in the French Alps, and found solace amongst the towering snowy peaks and the mossy woods, where I walked daily to both lose and find myself. I fly-fished in the surrounding lakes. On one occasion, sitting down on a colossal rock, I looked down on to Lac Cornu and wept. Unlike the tears I shed during lockdown, which were a sign that cracks were forming, however, this time my tears were restorative. Nature was healing me.

It could not, however, heal my scars. Every time I looked in the mirror at my scarred and battered body, I wondered what my younger self would have thought. Perhaps the initial shock would have been followed by the question: How will I hide all of them? The discomfort of seeing one’s body, wizened, is uncomfortable for anyone. But looking at the scars posed another question: Did I deserve this?

Acceptance: Looking for Beauty in Obscure Places

Over time, I have learnt that dwelling on my scars is no longer as important as facing the big questions which deserve to be answered about love, fear, self-worth, meaning and purpose. I have become more disciplined in looking for beauty in the most obscure places. And it’s the courage I have gathered to pause and face my mortality, to face the obvious: important realities are often the hardest to see and talk about. In that context, the scars don’t seem to matter as much as my younger self might have imagined. I consciously ask myself: What is important and what is not? That is perspective. And with that I have chosen to look at my scars differently.

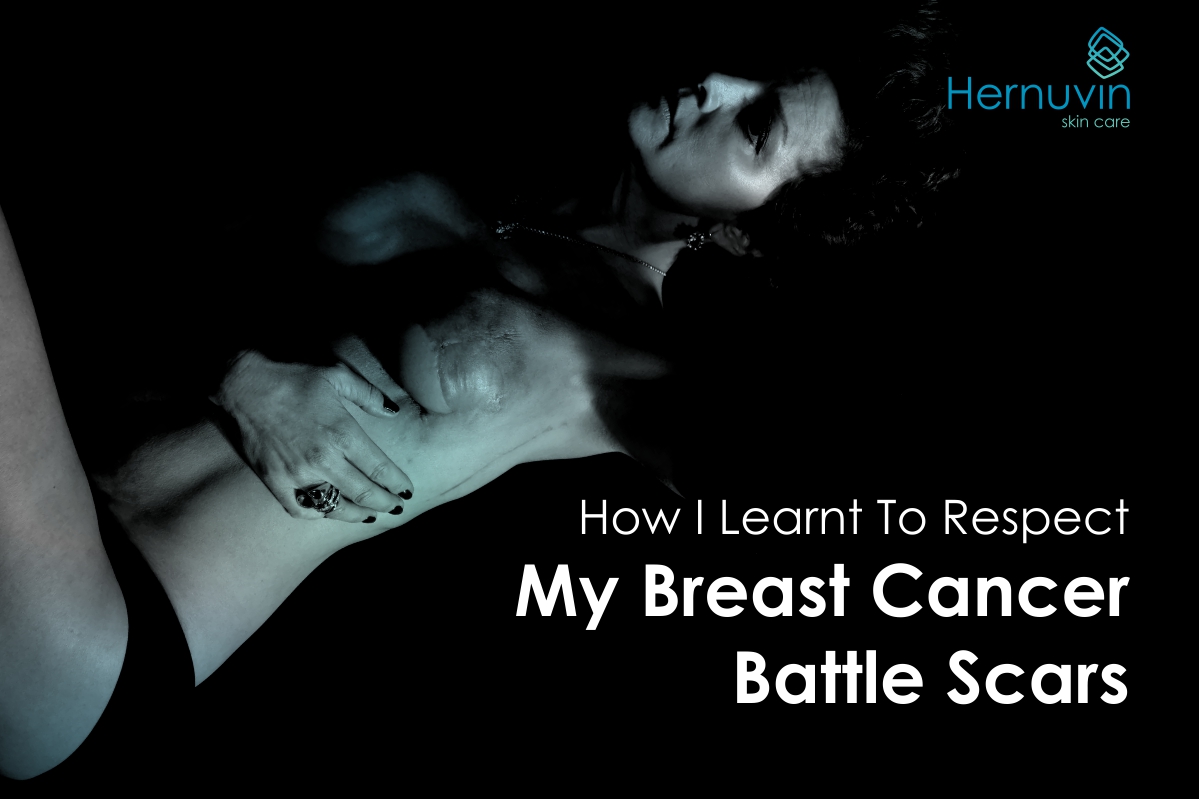

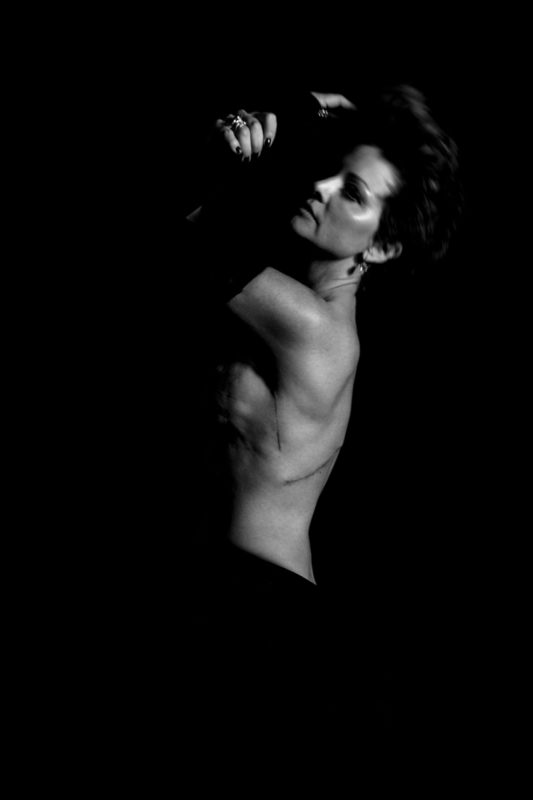

In January 2020, a photographer, Fred Bernard, suggested that he would like to take my portrait. I had never had my photograph taken professionally before, and I was terrified at the thought. But I was also feeling consumed with feelings of fraudulence: looking in the mirror at myself, undressed, was a reminder of the stark reality between what people see when they look at me, and what I know to be true.

Taking Off My Armour

Spurred on by a kind friend, I explained to Fred that I was undergoing treatment for breast cancer, and that I was struggling to come to terms with how my body looked. Prior to my double mastectomy, my breasts had been slowly increasing in size, with age, and the force of gravity had been a reminder that I wasn’t getting any younger. Strangely, pretty much the only perk of my reconstruction surgery was that the implants that were required subsequently gave me the breasts of a 20-year-old. But, I still struggled to look at the scars. I didn’t know that I would be able to take my armour off and show my body for what it was – but I hoped that the process of photographing my body might help me to comprehend what was happening, and to create a personal record of my journey.

Fred listened intently when I told him what I had been through, and then, after careful consideration, said: “I think this was meant to be.” He explained that he would like to impose an artistic quality on my experience which one doesn’t often see in the context of illness. We live in a time of filters, with any blemish or irregularity airbrushed out. But, trained under Fred’s camera, showing the cracks felt cathartic. My scars are not disfigurements, but marks of my struggle.

Kintsugi

When I look at the photographs today, I feel proud. I am reminded of kintsugi, a Japanese technique of mending broken pottery or glass by cementing the broken shards with powdered gold. In Japan, it is considered an art form to accentuate an object’s traumas. A broken bowl thus mended is more valuable than something intact.

What I’ve gone through is not unique. Certainly, you can attach a number to those who have walked in my shoes and no doubt it might be higher than you think. Conversely, each of us has a unique story to tell about how we worked through it – physical scars, emotional scars and all that comes with them.

Each step I have taken is mine. I carry these scars wherever I go and one facet of my story can be told through these photographs. Love them, loathe them – it is my way of telling my story.

[su_divider width=”full”]

Article References

BY KELLY HAIL

https://www.vogue.co.uk/beauty/article/breast-cancer-scarring

Kelly Hail is a patient advocate with the British Lymphology Society (BLS) dedicated to raising awareness about lymphoedema, a common complication of second-stage breast cancer. To find out more about lymphoedema and related lymphatic disorders, visit TheBLS.com.

[su_divider width=”full”]

WHY HERNUVIN SKIN CARE

[su_quote]The Hernuvin range is all about trying to help people address a true need, a need that is not necessarily only cosmetic or aesthetic.” – Dr Hugo Nel[/su_quote]

Medically designed and scientifically formulated by a specialist plastic surgeon (whose anaesthetist is a breast cancer survivor), Hernuvin is specifically formulated to address the side effects of Chemotherapy and traumatised skin.

Whether your skin is normal, showing the signs of ageing or recovering from the effects of chemotherapy and estrogen depletion, the Hernuvin Skin Care Range offers a simple skin care regime that facilitates the restoration of ailing skin, as well as providing effective prevention and protective assistance for all skin types.

[su_button url=”https://www.hernuvin.com/shop/” background=”#66c3bb” icon=”icon: heart”]Find out more about our skin care range[/su_button]